The immediate shocks in economic progress from demonetisation and GST have come to an end, and Indian growth is 7.5% for the next two years, but the nation wants an 8% plus GDP growth for 30 years if it is to join the mi income countries. It may be quite a challenge, as the recent experience indicates that, given India ‘s steady and robust economic growth, 8% growth lasted only one to two years, and in the following years it substantially rectified.

1. Natural Resources Management

The World Bank said India’s long-term growth is fundamentally restricted by the lack of natural resources. Also, if a resource-efficient development direction is followed, will India achieve an 8 per cent growth rate. In the aftermath of GST, reforms should focus on the cities to improve connectivity and transportation infrastructure and improve the provision of urban services; agriculture, by helping farmers avoid restrictions from the depletion of resources, improve the protection of water resources and focus reforms on the elimination of distortions in the electricity sector.

2. Employment Generation

The World Bank said that India needs to focus on sustainable, productivity-led growth that will provide the growing population of India with paid jobs. To do this includes improvement in two areas: creating a high-productivity investment environment that involves easing market bottlenecks, and changes will focus on developing skilled workers to meet the needs of the overall competitive industry.

3. Financial sector development

One of the government’s main objectives is to tackle the pressures of productivity in the public sector, to ensure that reforms are carried out successfully and to satisfy the demands of the increasing middle class. Reforms are not simply increased investment, but the improvement of governance in India. The changes should also concentrate on adequate resources for public service providers and on improving coordination between the different government levels, recalling the World Bank, in addition to improving the efficiency, efficacy, and transparency of the Indian public sector.

As the largest economy in the world in terms of buying parity, by 2030, India wants to improve the lives of all its citizens and become a country with high medium incomes. More than 90 million people have escaped extreme poverty between 2011-2015 and improved their standard of living with strong economic growth. In the past two years, however, India’s growth rate has slowed down.

In recent years, poverty rates have decreased dramatically, from 46% to 13,4% in the two decades before 2015. The poverty levels have been measured at 13,4%. Although India still has 176 million poor people, it strives to increase prosperity and to encourage inclusiveness and sustainability by reshaping human development policy strategies, social security, financial inclusion, rural transformation and construction of infrastructure.

While the development trajectory of the country is high, there remain challenges. There has been good economic growth, but advancement, gains in economic mobility, and exposure to resources that are different across demographic groups and geographical regions have been inconsistent. The speed at which poverty is reduced since 2015 may have been moderated by the difficulties raised by indirect tax reforms, pressures in the countryside, and high youth unemployment in urban areas. Amid regulatory changes to boost productivity, private spending and export rates also remain relatively small, and the possibility of longer-term growth is undermining. The human development indicators in the country, ranging from education results to a low and falling number of women employed – underline its significant development needs.

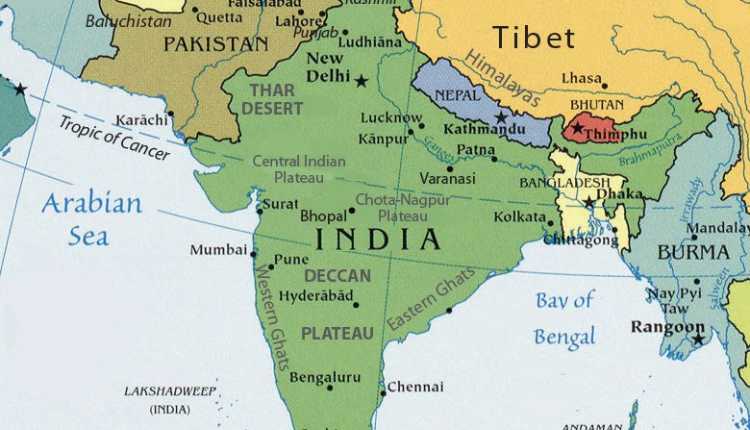

The neighbourhood of India comprising Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, which include Southeast Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries, is very complicated. That’s the least that can be said about Indians relations with neighbouring countries. Yes, India can be described as living in a dangerous place. Individually as well as individually, the constituent countries embody a web of ancient relations, cultural legacies, commonalities, and diversities that are so elaborately expressed in the ethnic, gender, religious and political structure of these countries. Even less complex is China and Myanmar, the two major neighbours.

There are also several inconsistencies, inequalities, and paradoxes in the southern Asian zone. Throughout the post-colonial period, South Asia became a site of bloodthirsty inter-State and civil wars; witnessed independence struggles, nuclear warfare, and military dictatorships, and continues to suffer as well as serious problems related to drug trafficking, religious fundamentalism, and terrorism. More than 540 mn people in the country still make up 44% of the poor in the developing world who earn less than $1.25 a day. The region has led many prominent woman politicians, but much remains to be accomplished overall for women’s empowerment. The constituent countries vary from inclusive secularism to strict fundamentalism concerning the barometer of religious freedom.

South Asia is the most less integrated regional association for 27 years. Yet, despite the Charter’s stipulation that “bilateral and contentious issues are excluded” from its deliberations, it allows dispute questions to be placed back and focusing on The South Asian Regional Cooperation Association (SAARC) remains in existence for more than 27 years.

It is maybe hard to write one particular foreign policy condition in an environment in which we have incorrigible Pakistan in one end and genuinely polite Bhutan in the other, and everyone else on the other end of the spectrum.

However, India has consistently sought to adopt and apply some fundamental approaches; for example:

- Despite such serious provocations as in the past (the assault on parliament, terrorist assaults in Mumbai, etc.), India advocates a policy of positive engagement. We claim the problems can only be compounded by brutal reprisals and conflict. This applies particularly to Pakistan, which is the source of state-sponsored Indian terrorism. However, it is not acceptable to misinterpret the engagement policy as vulnerability. Each time our endurance is checked, clear and loud signals will come from India.

- India adheres to its benevolent and Honorable stance of non-interference in the region’s internal affairs. Nonetheless, if any country has the potential to affect India’s national issues, whether accidental or malicious, then India doesn’t hesitate to respond quickly and quickly. Consider it: the intervention differs qualitatively from the intervention, especially when it is made at the request of the respective country.

- India’s foreign policy is largely decided at the national level. However, sometimes it seems that foreign policy is held hostage to domestic, regional policy. The most obvious examples are Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. Domestic sentiments and real concerns of the social segments must be taken into account but must not be permitted to depart from the foreign policy of the country, which must solely be directed and pursued in New Delhi by the overarching national interests.

- India tried to deal with the regime, be it a democracy, a monarchy, or a military dictatorship, and decided that it is better for the people of the country concerned to choose the form of government. India does not believe in promoting democracy, but does not hesitate to promote democracy wherever there is potential; this is achieved by fostering capacity building proactively and reinforcing democratic institutions;

- Economic and international policy objectives have been intertwined with today’s globalised world and can not be dealt with separately. One of India’s main foreign policy components is to create an external environment that is conducive to all-inclusive growth in the country. The partners in the region will be impressed by all diplomacy and political levers, which can lead to win-win conditions when joint explorations of natural resources are underway. India is an example to be quoted and followed in the cooperation with Bhutan in hydro-power generation. In contrast, Nepal remains a net importer of electricity, despite its huge hydro-resources, thanks to its reluctance to cooperate with India in this field.

- Indeed, since the beginning of the 1950s India has been using its policy on non-prescription aid as its soft power. In exchange, India searched for “goodwill” and “Indian friends.” In a short time, India is moving progressively from pure charity to a sensible combination of unqualified subsidies and soft loans linked to the export of projects and commodities. India is also working diligently to ensure that the ‘goodwill’ won in this manner is converted into actual political and economic dividends.

- Finally, India is prepared to take a further step towards inclusion in the region. As the International Financing Institutes also say, South Asia, can only be part of the Asian century through regional cooperation.

Independence was gained in India 71 years ago – on 15 August 1947. Over the intervening decades, the country has developed in a majorly the United States and its partners-led international system. Although Indian domestic and foreign policies were not easy to pursue in this system, the American rule was preferable to the British empire from which New Delhi was freed.

This economic structure is potentially under grave pressure. Washington, along with capital cities all over the European Union, is in a polarising dispute over their society’s social contracts, which left the US and its partners powerless to successfully protect world order principles in their domestic injustice and culture. Around the same moment, the balance of economic strength worldwide has tipped for Asia once more.

India has the potential to create a new paradigm within this changing global environment for its stability, growth, and prosperity, and the prosperity of developing countries around the world. This will be India’s major focus in the coming decades as a growing global power.

The changing Position in the international arena

At least two new trends have arisen from the unprecedented growth of Asian countries. Secondly, through economic cooperation, the political borders – many of which are colonial legacies – are becoming more and more vulnerable. Markets converge around the Eurasian territories and foster the Indian and Pacific Oceans’ Geo-economic union. The consequence is new challenges in terms of globalisation and new growth possibilities for populations, economies, and societies. Second, while economic relations have been acknowledged through geographical interests, political disparities are often reaffirmed – not just to question the hegemony of the past, but to form a new world.

India is economically mutually dependent but continues to develop politically as well; the region’s market-oriented expansion is incompatible with several political structures.

Part in China is responsible for both. China has been similarly committed to promoting freedom of trade, developing modern development capital and providing a new paradigm of globalisation and global governance while presenting a strongly opposed political outlook of “liberal international order.” India has an alarming possibility of China’s economic strength improving its expectations.

A New Order

Given the rapid transition that is underway, India ‘s challenge at Independence Day is to create a centenary of its independence on an inclusive and equitable international order. To achieve this, India must be able to function in the light of its capacity: by the middle of the century, the Political, industrial, economic, and strategic culture must be built for it to become the leading power. This could be seen as a model to emulate and anchor trust in the liberalism and internationalism of the world order in most developing countries.

Therefore, India demands a “consensus” – a new approach that not only guides its journey into the 21st century but also appeals to communities around the world.

Initially, India must sustain and strengthen its trajectory of fast economic growth and show to the world that, within the rubric of the liberal democracy, it can achieve its development goals. There can be no more strong and appealing reason for the New Delhi consensus than India’s economic performance. India accounts for 15 % of global growth according to IMF figures. Although nearly 40% of its population lives in different deprivation environments and only a third are wired to the internet, India nevertheless bears the world’s economic burden proportionately. Imagine global growth opportunities, if India can meet the Sustainable Development Goals ( SDGs) or even exceed them.

Developing countries are searching for repeated development models, but they have a bilateral alternative between Western liberalism, which is unacceptable for profoundly decentralised and politically stratified cultures, and autocratic regimes that have no room for independence for themselves.